The CAP in the News:

Project on schedule despite pandemic (Tribune Review, July 29, 2020)

Project continues on schedule (WESA, October 5, 2020)

Previous Posts in the Series:

Keeping an Eye on the CAP: Jun. 2020

The CAP in the News:

Project on schedule despite pandemic (Tribune Review, July 29, 2020)

Project continues on schedule (WESA, October 5, 2020)

Previous Posts in the Series:

Keeping an Eye on the CAP: Jun. 2020

Uptown in the News & on the Web:

President Trump tweets about BRT grant award (Post-Gazette, May 29, 2020)

Locust/Miltenberger Development Website

51-unit apartment proposed in 1700 block of Fifth Avenue (Pittsburgh Business Times, June 1, 2020)

$99.95 million awarded for BRT (Next Pittsburgh, June 2, 2020)

Funding awarded for proposed mixed-use with affordable housing project (Pittsburgh Business Times, August 18, 2020)

BRT service may start in 2023 (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 21, 2020)

Solidarity murals coming to the city (Next Pittsburgh, September 27, 2020)

Gentrification concerns raised for proposed tech development (Pittsburgh Business Times, September 30, 2020)

Interview with developer of proposed Uptown mixed-use project (Pittsburgh Business Times, October 5, 2020)

Partner pulls out of Fifth and Dinwiddie project (Pittsburgh Business Times, October 26, 2020)

Planning Commission approves Uptown tech development (Public Source – Develop PGH Bulletins, October 27, 2020)

Commercial portion presented for Fifth and Dinwiddie project (Pittsburgh Business Times, November 10, 2020)

Previous posts in series:

Keeping an Eye on Uptown: May 2020

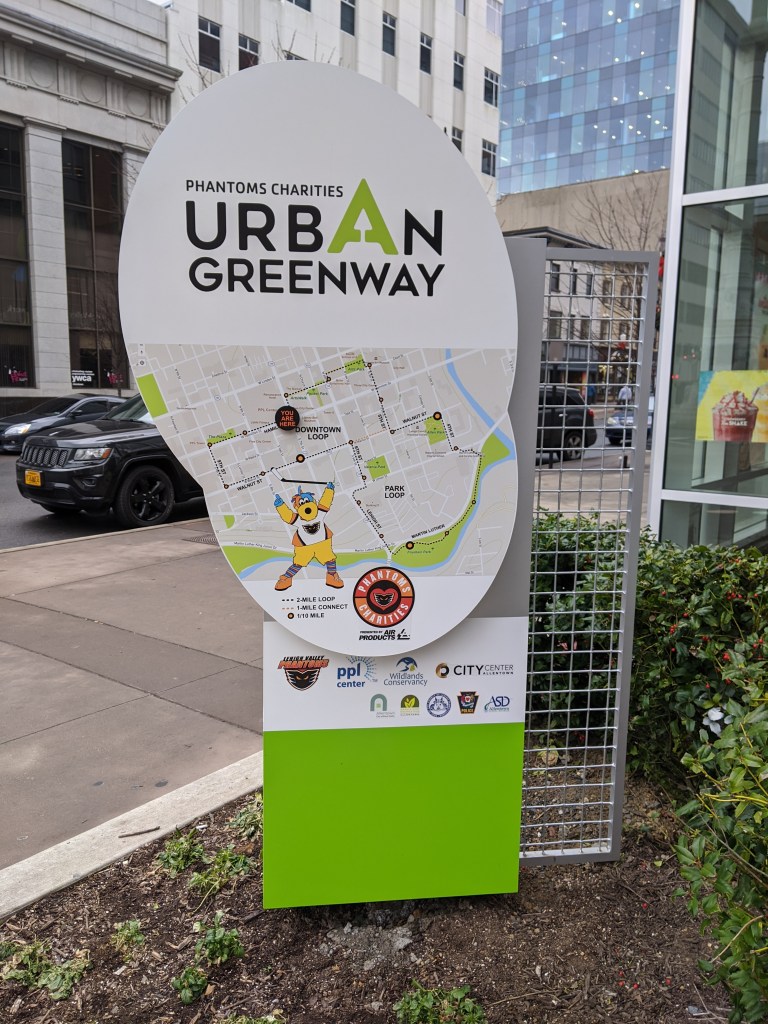

Allentown, PA, had been on my travel list for years because of the awards and acknowledgements it was receiving from the planning community (and because I grew up near there). When I finally visited, the only thing that engaged my interest was the Liberty Bell Museum. There was a stark contrast between the cohesion and vibrancy of Bethlehem’s main street, where I stayed, and the hodge-podge of Allentown’s main street. The proportions in Allentown felt all wrong. In the core, the roads and sidewalks felt too narrow for the density and height of the buildings. At odd moments, this claustrophobic spacing suddenly opened out into large vacant plazas with buildings placed far from the road. After the pleasant surprise of Bethlehem’s tree-lined, historic business district with wide sidewalks for promenading and window shopping (and now social distancing), Allentown was a disappointment.

However, since being home, I find I have a growing appreciation for one of Allentown’s newer developments. The PPL Center gave me a sterile vibe at the time. I only glanced at the façade as I investigated the map out front with recommended lunchbreak walks and the historic building next door. From the outside, the partial attention I gave the center suggested a shopping or office complex. It wasn’t until I accidentally entered the lobby and saw the stadium seating beyond the ticket booth that I realized it was an arena. Perhaps due to my distraction at the time, it was only in the comfort of my home that I registered my shock over finding an arena that managed the rare feat of fitting into its surroundings.

Pittsburgh’s arenas have done the opposite. For decades, there was the Civic Arena that looked like a spaceship plopped down in the middle of a city spewing parking lots out from the landing center. A flagship of Pittsburgh’s Urban Renewal, it has since been demolished with the plan to rebuild the urban fabric on the site to reconnect the Hill District to downtown. The replacement arena made some attempts to fit in more with its neighborhood. It is built up to the sidewalk or, rather, the sidewalk is built up to it creating a large sea of concrete out of proportion with the sidewalks opposite. The principal street façade includes one restaurant open to anyone inside or outside the arena during normal restaurant hours, though I don’t recall ever seeing anyone eating at their sidewalk café (even before quarantine and social distancing). Instead, the restaurant feels like a weird mistake pasted onto the building’s towering blank wall.

In contrast, the street facing restaurants in Allentown’s arena are part of the reason I mistakenly identified the structure as a retail and office building. They felt like places with lives of their own, independent of special events. The plaza in front of the arena is proportional to the plaza on the adjacent corner. The building is built up to the sidewalks with the same building height and sidewalk width as the surrounding urban fabric. As a result, this arena blends into its neighborhood, such as it is.

While exploring Bethlehem’s bridges, my eye was caught by the numerous spires rising above the surrounding buildings of South Bethlehem. Instead of resting upon returning to the hotel, I felt compelled to go back out and take a survey of religious buildings within walking distance. Due to the topography, those on the slopes of South Bethlehem were the easiest to spot, but I also located some in Bethlehem’s historic district and in West Bethlehem. I found twenty-three buildings in all.

As with my experience in Erie, I was surprised that the vast majority of these buildings were still open for use as religious worship. Bethlehem Steel Company was the main employer in Bethlehem for most of the 20th Century. Like steel mills elsewhere in the northeast, its business declined. In the early 2000s, the company went bankrupt. This makes it seem like the town should have experienced the classic rise and decline of other Rust Belt Cities.

One of the typical landmarks of this change is an abundance of vacant or adaptively reused religious buildings. In Pittsburgh, I have found over 50 former churches and synagogues now being used for secular purposes or in the process of being converted to secular purposes. Many more are vacant and boarded. Wilkinsburg, a town adjacent to Pittsburgh, has so many closed churches that its zoning code incorporates guidelines for converting church buildings to secular uses. Homestead, PA, the former home to US Steel and the site of the famous Homestead Steel Strike, has several shuttered churches. Bethlehem’s religious buildings did not fit this pattern.

In searching for an answer to what made Bethlehem different than other steel towns, I realized that the business districts and residential areas I passed through were mostly intact. There were few vacant buildings and no vacant and abandoned grass lots. This suggested that Bethlehem did not experience the same decline as the other former steel towns that I have explored. The historical population data corroborated this hypothesis. Bethlehem and Erie experienced their peak populations in 1960; Pittsburgh and Wilkinsburg in 1950; and Homestead in 1920. In 2010, the cumulative population loss from each city’s peak was:

| City | Population Loss |

| Bethlehem | 1% |

| Erie | 26% |

| Pittsburgh | 55% |

| Wilkinsburg | 49% |

| Homestead | 85% |

The stable population of Bethlehem explains why so many religious institutions are still operating. It doesn’t explain why the people stayed when the jobs left.

I picked up Jeffrey A Parks’s “Stronger than Steel: Forging a Rust Belt Renaissance” to look for clues to what made Bethlehem different from other Rust Belt cities. For the most part, it seems to have pursued the same actions and initiatives as elsewhere. Bethlehem’s leaders even hired consultants from Pittsburgh in the 1950s to learn how to do Urban Renewal. Other similarities include the creation of a redevelopment authority, the use of eminent domain to force people out of their homes for commercial development, the building of a highway through town, and the change of traffic patterns to prioritize the regional over the local.

The one thing mentioned in Parks’s book that was different from other cities was the school district. In the 1960s, the Bethlehem School District expanded to incorporate two rural townships. These townships later became wealthy suburbs that combined with the population of Bethlehem to create a racially and economically diverse district. Parks’s implication seemed to be that the result was a school district with better funding and resources than its neighbors. Perhaps, as a result, families did not have the conversation about moving to the suburbs for better schools as their children approached school age.

A decent inner-city school district may reduce the flight to the suburbs. It also may attract new residents. Yet, I wonder if it is enough to prevent hemorrhaging population loss as a region’s major employer cuts jobs in the decades before it closes.

Street trees have a tough life. Between extensive pruning away from power, cable, and internet lines, baking in the radiant heat from the surrounding pavement, and (in winter climates) runoff from salt or sand, it is amazing any survive. Yet in some neighborhoods street trees are thriving while in others they are non-existent or barely hanging on.

Street trees first appeared in US cities in the 1840s and 1850s as part of a growing interest in landscape architecture. However, they soon encountered challenges. Fire insurance companies banned street trees in towns that relied on bucket brigades as the trees helped spread fires that decimated swaths of towns. Then, the street trees worst nemesis arrived – the overhead lines. First telephone companies then power companies pruned trees away from their lines. John R. Stilgoe in Outside Lies Magic notes that the resultant loss of street trees created a “nationwide uproar” by 1920. One hundred years later, this conflict between wires and trees is still unresolved.

As I traveled around Pittsburgh this spring and summer, I noticed that some neighborhoods seem to have found a way to maintain both old, large canopy street trees and overhead lines. Other neighborhoods appear to struggle to establish and maintain even understory or decorative trees. The pattern of where street trees are thriving versus where they aren’t appears to match the wealth of the neighborhood.

I first noticed this pattern as a child, though I couldn’t articulate it as such at the time. The Pennsylvania town where I partially grew up had a Green Street. The name made a strong impression on me at the time because half of Green Street was very aptly named. It had the oldest and thickest street tree canopy in town. The other half of the street, as I remember it, did not have a single street tree (or yard tree). This dichotomy fascinated me as a child.

Now, looking back on this memory with my urbanist eyes, it seems the perfect example of the correlation between wealth and street trees. The half of Green Street with the street trees was predominantly detached, single-family dwellings with large front, side, and rear yards. The half of Green Street without street trees was predominantly attached homes, possibly with some duplexes, and shallower front yards.

In Pittsburgh, the division is by neighborhood, not block. Neighborhoods like Squirrel Hill, Point Breeze, and Shadyside, which used to contain most of the city’s millionaires rows and continue to have housing values 3-4 times the city’s average, have old, well-established street trees that are somehow able to grow around the overhead lines. Neighborhoods like Homewood and the Hill District, which were victimized by Urban Renewal policies in the ‘50s and ‘60s and now have housing values two-thirds the city’s average, have few street trees, most of which were planted within the last ten years.

Hazelwood is a neighborhood divided in two by railroad tracks. On one side of the tracks are Hazelwood Green, a residential enclave, and some industrial and commercial uses. This is what is across the tracks:

Second Ave

Hazelwood Ave

Other Sites

Hazelwood in the News:

New Businesses Revitalizing Second Ave (Next Pittsburgh, November 21, 2019)

URA Picks Community Builders for Affordable Housing Development on Second Ave (Pittsburgh Business Times, January 15, 2020)

Study Pushes Multi-modal Transit Improvements to Hazelwood’s 2nd Avenue (Post-Gazette, February 10, 2020)

Report Says Traditional Buses Better for Hazelwood than Autonomous Shuttles (City Paper, April 21, 2020)

Restaurants Reopen – Diners Return (Post-Gazette, June 28, 2020)

66 New Homes Proposed (Pittsburgh Business Times, September 10, 2020)

Previous posts in series:

Keeping an Eye on Hazelwood (across the tracks): Apr. 2020

Keeping an Eye on Hazelwood: Introduction

Hazelwood is a neighborhood divided in two by railroad tracks. This is what is on the same side of the railroad tracks as Hazelwood Green, but on the other side of the black fence surrounding the Uber test track:

Hazelwood in the news:

The Progress Fund Proposes Turning a Former Brewery into a Craft Brewpub Hub (Pittsburgh Business Times, July 31, 2020)

Previous posts in series:

Keeping an Eye on Hazelwood: May 2020

Keeping an Eye on Hazelwood: Introduction

I regret not starting this series on the former Penn Plaza site sooner. I missed opportunities to photograph the former apartments in their neglected, partially occupied state and the demolition of the buildings. Starting with the project several months into construction is a case of better late than never and provides an opportunity to watch how the promise to rebuild the neighborhood park becomes fulfilled.

Penn Plaza in the News

Evictions 2015-2019:

Evictions Highlight Lack of Affordable Housing (City Paper, July 22, 2015)

Residents Meet About Eviction Notices (New Pittsburgh Courier, July 23, 2015)

Evictions Set Standard for Future (WESA, February 29, 2016)

Owners and Displaced Tenants Work out Deal (WTAE, February 29, 2016)

Final Residents Move Out (WESA, March 31, 2017)

Mass Evictions (Downstream, February 15, 2018)

Protesters Call for Action Years After Evictions (KDKA, July 28, 2018)

Dark Stain on the City (Pittsburgh Current, July 30, 2018)

Defining Community (Public Source, September 27, 2019)

Negotiations 2017-2019:

Penn Plaza Support and Action Blog

City, Community, Developer Reach Agreement (WESA, October 27, 2017)

Final Go-Ahead Approved (Post-Gazette, February 12, 2019)

City Seeks Land Swap (WESA, October 4, 2019)

Controversy Continues with Land Swap Proposal (Tribune Review, October 15, 2019)

City Fails to Keep Promises (WESA, October 23, 2019)

City Falling Short on Guarantees (Post-Gazette, October 28, 2019)

Residents Concerned About Park Reconfiguration (Tribune Review, October 28, 2019)

Construction 2019-current:

City Council Clears the Way (WESA, October 29, 2019)

Construction Starts (Pittsburgh Business Times, October 30, 2019)

Groundbreaking Announced for December 2019 (Next Pittsburgh, October 30, 2019)

Hazelwood Green in the News:

Roundhouse Renovation Next For Hazelwood Green (Next Pittsburgh, January 26, 2020)

Locomotive Roundhouse to Host Co-working Space (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 28, 2020)

Tenant Landed for Roundhouse (Pittsburgh Business Times, February 25, 2020)

From Blight to Tech Node? (CoStar, June 3, 2020)

Largest Solar Installation (Next Pittsburgh, June 29, 2020)

Hazelwood Green – Mill 19 Building A Named 2020 Best Project (ENR MidAtlantic, July 29, 2020)

Largest Solar Installation Completed (Solar Power World, August 13, 2020)

Drive-In Arts Festival at Hazelwood Green (Twitter, August 13, 2020)

Previous posts in series: