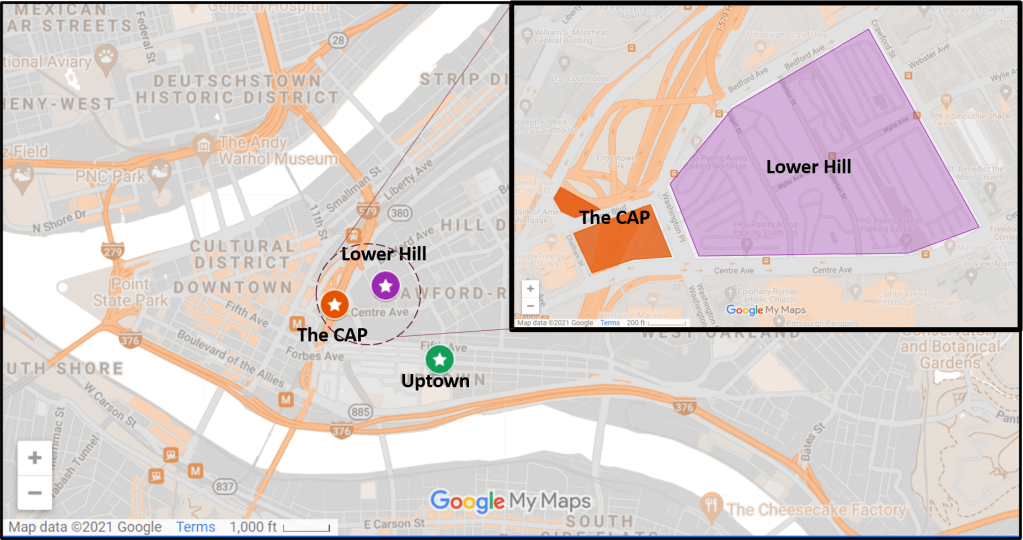

The CAP is a project in Pittsburgh “fixing the mistakes” of Urban Renewal. The Crosstown Blvd was built in the 1960s creating a freeway in a canyon dividing the Lower Hill neighborhood from downtown. The Lower Hill neighborhood, formerly predominantly poor and black, had already been demolished by this point to make way for the Civic Arena and other cultural amenities that were never built.

The CAP is a park on a bridge being built over the Crosstown Blvd and is intended to reconnect downtown and the Lower Hill, while the Lower Hill is being rebuilt by the Penguins hockey team. Construction began in June 2019 and was expected to be completed in November 2021. As the photos below show, it appears to be predominantly completed mid-November 2021, but the construction fence was still up. There are still a couple weeks left in the month to meet the project schedule. There do not appear to be any news articles about this project since the May post of Keeping an Eye on the CAP. The next bit of news about the site will probably be either announcing the ribbon cutting or a project delay.

This post is part of an on-going photographic series to watch the development and usage patterns of the CAP. Periodically, approximately once every six months, I return to the site to take new photographs. At the end of the post, there are links to all the previous posts in the series.

Previous Posts in the Series:

Keeping an Eye on the CAP: May 2021

Keeping an Eye on the CAP: Dec. 2020

Keeping an Eye on the CAP: Jun. 2020