Pittsburgh DinoMite Parade 5

Kittanning is a small town of just under 4,000 residents on the Allegheny River northeast of Pittsburgh. The name is from a Native American village destroyed in 1756 and is thought to mean “the place at the Great River.” It has a single bridge, the Kittanning Citizens Bridge, which was built in 1932 and renovated in 2010. According to historicbridges.org, “In a rare gesture of good faith to taxpayers and preservationists, PennDOT has made the logical decision to rehabilitate this bridge rather than demolish and replace it.” So while this bridge was an unplanned stop on my weekend wanderings and in my blog schedule, it fits nicely with the current theme of demolish & replace or renovate.

The northeastern shore (the Kittanning side) has a nice waterfront park with a boat launch, amphitheater, upper and lower walking paths, fishing and seating areas, and seasonal public restrooms. The southeastern shore (the West Kittanning side) has some houses set back across a road looking out toward the river.

After my disappointment in trying to reach the lakefront at Grant Park, I had given up on reaching the shore on that trip. The weather had been perfect (being August instead of April), but it seemed I was fated to not wade in the lake.

However, after exploring the former site of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair in Jackson Park, I was making my way to a bus stop to return to my hotel and found myself on a path to the 63rd Street Beach. Lake Shore Drive still continued along the lake’s shore, but it was not an obstacle here as it bridged over the pedestrian trail.

While mounting frustration had turned me back from the lake in Grant Park, the ease of following Jackson Park’s meandering trail turned me away from my original goal to add a stop at the lake beach. The beach house suggested days of better maintenance and greater usage, but the beach and adjoining greenspace appeared to be a pleasant amenity for local traffic.* While tourists may have found their way there in 1893, I seemed to be the only one when I visited.

*My tendency to take photos of things rather than people presented a missed opportunity when picking photos for this post. There were several small groups of people on the beach and more carloads of people enjoying picnics on the other side of the beach house. Yet, none of the photos I took that day included any of these people.

While exploring the Grant Park viaducts on my 2019 trip to Chicago, I discovered that they were connected to promenades leading to the lake. I decided to wend my way through Grant Park by strolling down one promenade to the lake and another back to Michigan Avenue and so on, weaving back and forth. It turns out that this is no longer an option.

On the 1920s map that inspired me to visit the viaducts, the only divider in Grant Park was the railroad tracks bridged by the viaducts. The rest of the park showed on the map as a vast open space where I assumed the promenades were designed for wealthy residents and visitors to take the air and see who else was in town (or perhaps that is just the influence of reading Jane Austen so much). While it didn’t matter to me who else was in town, strolling along the promenades seemed a nice way to take the air.

Whatever the original intent, today the promenades are chopped up by their modern antithesis – the multi-lane, high speed road. While there are several promenades spaced throughout the park, I only found one that had a protected pedestrian crossing over the many lanes of Columbus Drive. Clearly, this was the grand promenade. In addition to being the only one with a safe passage, past Columbus it featured an opulent water fountain.

Having already crossed a significant barrier, I assumed it would be a clear walk to the waterfront after that point. However, on the other side of the fountain, I found the even more formidable barrier of Lake Shore Drive, aka Route 41. All interest in continuing with my promenade evaporated even though the lights and crosswalks suggested the ability to cross safely. Instead, I spent some time admiring the fountain before returning to my hotel.

I was disappointed at discovering that the connection between the park and the lake was an optical illusion. Yet, it came as no surprise to find the lake front prioritized for cars. It is a recurring experience to find an urban waterfront cut off from the rest of the city by a major roadway barrier, or in this case two.

Allentown, PA, had been on my travel list for years because of the awards and acknowledgements it was receiving from the planning community (and because I grew up near there). When I finally visited, the only thing that engaged my interest was the Liberty Bell Museum. There was a stark contrast between the cohesion and vibrancy of Bethlehem’s main street, where I stayed, and the hodge-podge of Allentown’s main street. The proportions in Allentown felt all wrong. In the core, the roads and sidewalks felt too narrow for the density and height of the buildings. At odd moments, this claustrophobic spacing suddenly opened out into large vacant plazas with buildings placed far from the road. After the pleasant surprise of Bethlehem’s tree-lined, historic business district with wide sidewalks for promenading and window shopping (and now social distancing), Allentown was a disappointment.

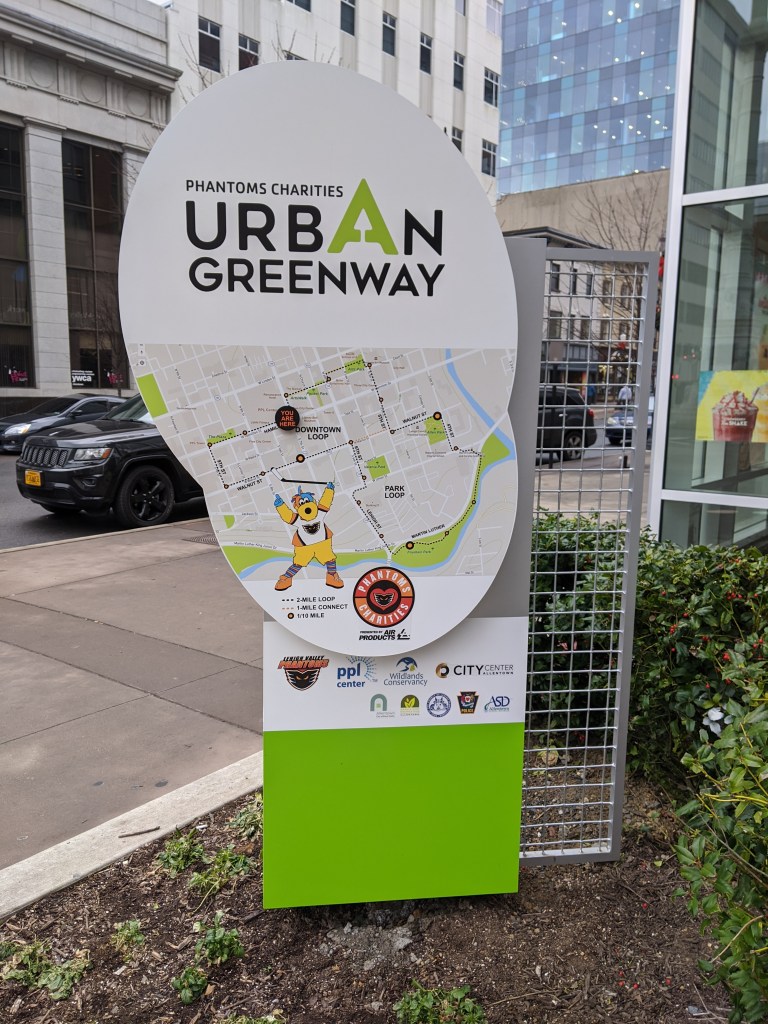

However, since being home, I find I have a growing appreciation for one of Allentown’s newer developments. The PPL Center gave me a sterile vibe at the time. I only glanced at the façade as I investigated the map out front with recommended lunchbreak walks and the historic building next door. From the outside, the partial attention I gave the center suggested a shopping or office complex. It wasn’t until I accidentally entered the lobby and saw the stadium seating beyond the ticket booth that I realized it was an arena. Perhaps due to my distraction at the time, it was only in the comfort of my home that I registered my shock over finding an arena that managed the rare feat of fitting into its surroundings.

Pittsburgh’s arenas have done the opposite. For decades, there was the Civic Arena that looked like a spaceship plopped down in the middle of a city spewing parking lots out from the landing center. A flagship of Pittsburgh’s Urban Renewal, it has since been demolished with the plan to rebuild the urban fabric on the site to reconnect the Hill District to downtown. The replacement arena made some attempts to fit in more with its neighborhood. It is built up to the sidewalk or, rather, the sidewalk is built up to it creating a large sea of concrete out of proportion with the sidewalks opposite. The principal street façade includes one restaurant open to anyone inside or outside the arena during normal restaurant hours, though I don’t recall ever seeing anyone eating at their sidewalk café (even before quarantine and social distancing). Instead, the restaurant feels like a weird mistake pasted onto the building’s towering blank wall.

In contrast, the street facing restaurants in Allentown’s arena are part of the reason I mistakenly identified the structure as a retail and office building. They felt like places with lives of their own, independent of special events. The plaza in front of the arena is proportional to the plaza on the adjacent corner. The building is built up to the sidewalks with the same building height and sidewalk width as the surrounding urban fabric. As a result, this arena blends into its neighborhood, such as it is.

While looking for churches on Bethlehem’s South Side, I discovered fun, colorful planters lining the business district’s streets. I photographed 25 that were along my path, though there were many others if I had taken time to continue wandering.

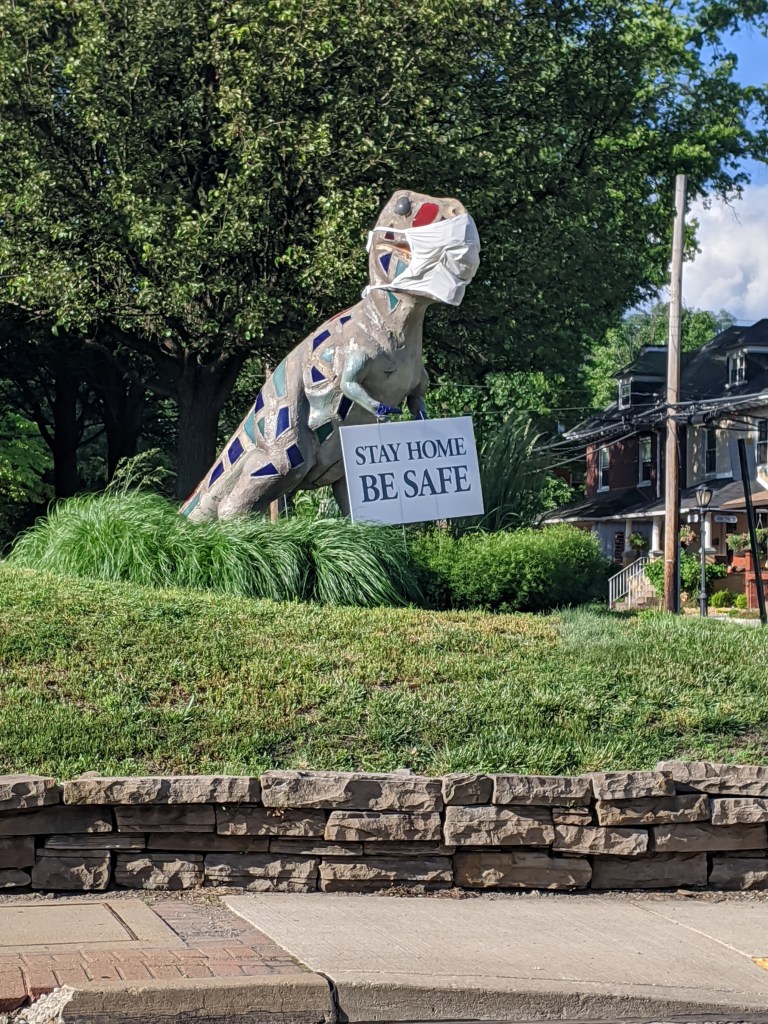

The planters are a beautification project of Bethlehem’s South Side Arts District Main Street Program. Pittsburgh gets a shout-out as inspiration for the arts work of this organization, but I think they’ve surpassed Pittsburgh with this project. While Pittsburgh has various murals and hosted a dinosaur fiberglass fundraiser during that fad, it doesn’t have initiatives to turn everyday street objects into public art canvases. I’ve enjoy stumbling across these everyday artworks in Bethlehem and Harrisburg.

While exploring Bethlehem’s bridges, my eye was caught by the numerous spires rising above the surrounding buildings of South Bethlehem. Instead of resting upon returning to the hotel, I felt compelled to go back out and take a survey of religious buildings within walking distance. Due to the topography, those on the slopes of South Bethlehem were the easiest to spot, but I also located some in Bethlehem’s historic district and in West Bethlehem. I found twenty-three buildings in all.

As with my experience in Erie, I was surprised that the vast majority of these buildings were still open for use as religious worship. Bethlehem Steel Company was the main employer in Bethlehem for most of the 20th Century. Like steel mills elsewhere in the northeast, its business declined. In the early 2000s, the company went bankrupt. This makes it seem like the town should have experienced the classic rise and decline of other Rust Belt Cities.

One of the typical landmarks of this change is an abundance of vacant or adaptively reused religious buildings. In Pittsburgh, I have found over 50 former churches and synagogues now being used for secular purposes or in the process of being converted to secular purposes. Many more are vacant and boarded. Wilkinsburg, a town adjacent to Pittsburgh, has so many closed churches that its zoning code incorporates guidelines for converting church buildings to secular uses. Homestead, PA, the former home to US Steel and the site of the famous Homestead Steel Strike, has several shuttered churches. Bethlehem’s religious buildings did not fit this pattern.

In searching for an answer to what made Bethlehem different than other steel towns, I realized that the business districts and residential areas I passed through were mostly intact. There were few vacant buildings and no vacant and abandoned grass lots. This suggested that Bethlehem did not experience the same decline as the other former steel towns that I have explored. The historical population data corroborated this hypothesis. Bethlehem and Erie experienced their peak populations in 1960; Pittsburgh and Wilkinsburg in 1950; and Homestead in 1920. In 2010, the cumulative population loss from each city’s peak was:

| City | Population Loss |

| Bethlehem | 1% |

| Erie | 26% |

| Pittsburgh | 55% |

| Wilkinsburg | 49% |

| Homestead | 85% |

The stable population of Bethlehem explains why so many religious institutions are still operating. It doesn’t explain why the people stayed when the jobs left.

I picked up Jeffrey A Parks’s “Stronger than Steel: Forging a Rust Belt Renaissance” to look for clues to what made Bethlehem different from other Rust Belt cities. For the most part, it seems to have pursued the same actions and initiatives as elsewhere. Bethlehem’s leaders even hired consultants from Pittsburgh in the 1950s to learn how to do Urban Renewal. Other similarities include the creation of a redevelopment authority, the use of eminent domain to force people out of their homes for commercial development, the building of a highway through town, and the change of traffic patterns to prioritize the regional over the local.

The one thing mentioned in Parks’s book that was different from other cities was the school district. In the 1960s, the Bethlehem School District expanded to incorporate two rural townships. These townships later became wealthy suburbs that combined with the population of Bethlehem to create a racially and economically diverse district. Parks’s implication seemed to be that the result was a school district with better funding and resources than its neighbors. Perhaps, as a result, families did not have the conversation about moving to the suburbs for better schools as their children approached school age.

A decent inner-city school district may reduce the flight to the suburbs. It also may attract new residents. Yet, I wonder if it is enough to prevent hemorrhaging population loss as a region’s major employer cuts jobs in the decades before it closes.