Allentown, PA, had been on my travel list for years because of the awards and acknowledgements it was receiving from the planning community (and because I grew up near there). When I finally visited, the only thing that engaged my interest was the Liberty Bell Museum. There was a stark contrast between the cohesion and vibrancy of Bethlehem’s main street, where I stayed, and the hodge-podge of Allentown’s main street. The proportions in Allentown felt all wrong. In the core, the roads and sidewalks felt too narrow for the density and height of the buildings. At odd moments, this claustrophobic spacing suddenly opened out into large vacant plazas with buildings placed far from the road. After the pleasant surprise of Bethlehem’s tree-lined, historic business district with wide sidewalks for promenading and window shopping (and now social distancing), Allentown was a disappointment.

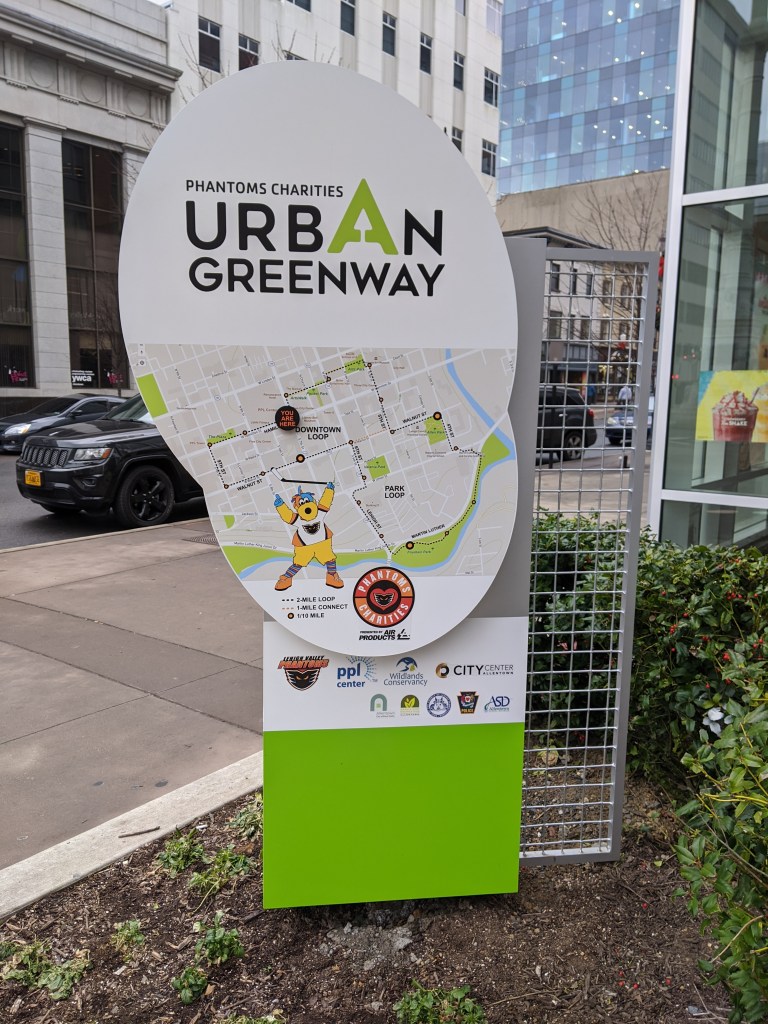

However, since being home, I find I have a growing appreciation for one of Allentown’s newer developments. The PPL Center gave me a sterile vibe at the time. I only glanced at the façade as I investigated the map out front with recommended lunchbreak walks and the historic building next door. From the outside, the partial attention I gave the center suggested a shopping or office complex. It wasn’t until I accidentally entered the lobby and saw the stadium seating beyond the ticket booth that I realized it was an arena. Perhaps due to my distraction at the time, it was only in the comfort of my home that I registered my shock over finding an arena that managed the rare feat of fitting into its surroundings.

Pittsburgh’s arenas have done the opposite. For decades, there was the Civic Arena that looked like a spaceship plopped down in the middle of a city spewing parking lots out from the landing center. A flagship of Pittsburgh’s Urban Renewal, it has since been demolished with the plan to rebuild the urban fabric on the site to reconnect the Hill District to downtown. The replacement arena made some attempts to fit in more with its neighborhood. It is built up to the sidewalk or, rather, the sidewalk is built up to it creating a large sea of concrete out of proportion with the sidewalks opposite. The principal street façade includes one restaurant open to anyone inside or outside the arena during normal restaurant hours, though I don’t recall ever seeing anyone eating at their sidewalk café (even before quarantine and social distancing). Instead, the restaurant feels like a weird mistake pasted onto the building’s towering blank wall.

In contrast, the street facing restaurants in Allentown’s arena are part of the reason I mistakenly identified the structure as a retail and office building. They felt like places with lives of their own, independent of special events. The plaza in front of the arena is proportional to the plaza on the adjacent corner. The building is built up to the sidewalks with the same building height and sidewalk width as the surrounding urban fabric. As a result, this arena blends into its neighborhood, such as it is.