Adrenaline is a powerful force. When I arrived in Vancouver in 2016, I bounded with energy despite only having slept 4 hours in the previous 36. After dropping my stuff off at my lodgings, I rented a bike and rode like a woman on a mission along the waterfront trail. Part of that mission was to burn off the adrenaline so that I would be able to sleep that night.

However, revisiting my photos and my recollections of this trip to write about the bridges and greenery, I’ve been haunted by the thought that there was an additional mission to that bike ride. I distinctly remember biking the trail along False Creek, but I have no photos from this excursion (the photo above is False Creek from Granville Bridge, nowhere near Olympic Village). Perhaps I was too focused on my mission? One line from my travel journal buried in a flurry of thoughts on urban design reminded me that the destination of that bike ride was the Olympic Village from when Vancouver hosted the 2010 Olympics.

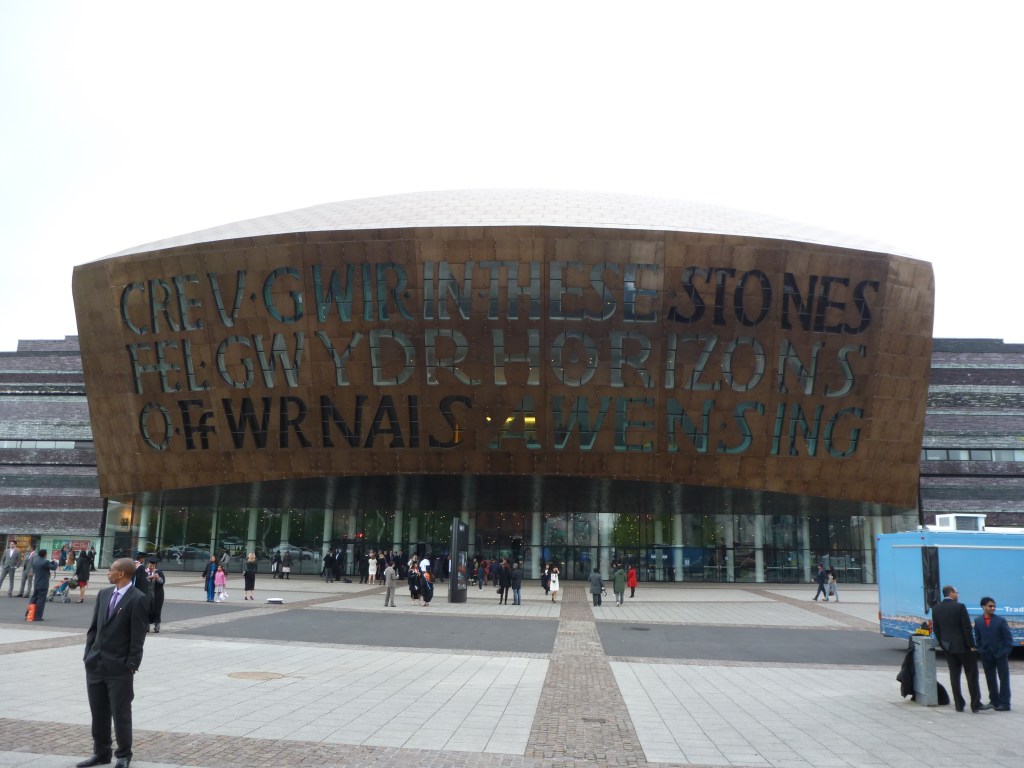

In my journal reflecting on the city’ newer architecture that could have been anywhere, I wrote: “In biking along the coastal trail, there were several parts that I felt could have been Cardiff or London. For instance, the part around Yaletown felt like the Cardiff Wharf development, though this one melded into its surroundings on all sides unlike Cardiff’s which was just plopped there. The area around Olympic Village and parts also around Yaletown felt a lot like the part of London past the Tower Bridge on the southern shore.” (Photos of the area around Tower Bridge are below and, of course, the building that I remember as being what I probably was thinking of in Vancouver is not one I photographed.)

My interest in the Olympic Village came from the same place as my on-going interest in World Fairs and Urban Renewal. These are large-scale developments that cities pursue “for the greater good” to attract tourists and others outside their boundaries while ignoring or actively harming their residents. Despite the intent, the end result is often more harm than good. For example, the Olympics and World Fairs are typically promoted as events that will bring in extensive revenues to the city, but most lose money due to the large expenditures required to build the necessary facilities. A successful Fair or Olympics is the one that breaks even.

In my Comparative International Urbanism course in college, I wrote a paper on three large-scale redevelopments in London, including the Olympic Village from the 2012 summer games. I intended to visit the Olympic Village when I visited London that May, but I got distracted by bridge walking. The research I did for that paper on Olympic Villages highlighted the inequities inflicted on residents in the construction of these developments. Based on my paper, over 200 local businesses and nearly 1,000 residents were evicted for London’s Olympic Village.

While I can’t find my notes, I seem to recollect that researchers featured Vancouver as the city whose Olympic Village created the least harm for existing residents and most seamlessly integrated into city life after the games and athletes left. Something I definitely would have wanted to see while in Vancouver, but I was operating on too little sleep to take photos to prove I was there.